Friday marks 10 years since a Ferguson police officer shot and killed 18-year-old Michael Brown Jr. The killing and the decision not to charge the officer sparked protests and riots across the nation, led to a U.S. Department of Justice investigation that revealed racially biased policing, and catapulted the Black Lives Matter movement into the mainstream through social media. 383o26

The decade since that August afternoon has seen a reckoning of policing and court practices in Ferguson, division surrounding the facts of Brown’s death, and efforts to rebuild the community.

In Ferguson: A Decade Later, First Alert 4 looks at the major changes in Ferguson and the St. Louis region because of Brown’s death.

After 8 years of federal oversight, judge sees ‘real change’ in Ferguson 2f1c1l

By Pat Pratt

With the 10th anniversary of the police shooting of Michael Brown on the horizon, U.S. Senior District Judge Catherine Perry spoke in July to the parties gathered in her courtroom on what, in her eyes, has changed in the city of Ferguson since August 9, 2014.

It was a hearing that has become commonplace since Brown’s death, a quarterly update on the consent decree between the Department of Justice and the City of Ferguson, an agreement which in Perry’s words, seeks to give everyone the kind of policing they deserve.

“And I guess I would echo what others have said here today, that the changes that are happening in Ferguson, in the court system and in the police system and in the engagement with the community, these are things that are necessary for fully providing the constitutional rights that the Constitution guarantees to all citizens,” Perry said.

Consent decrees have in recent decades become the go-to for reforming troubled law enforcement agencies. In the case of Ferguson, the agreement requires a substantial change in the city’s justice system, from how fines are paid to how officers on the beat interact with the public.

While Brown’s death is not directly related to the consent decree, his death spurred the investigation which found Ferguson violated the U.S. Constitution in the way it enforced the law. The DOJ released its findings in March 2015 and in April 2016 it entered into the agreement with Ferguson.

Brown and a friend were walking on Canfield Drive on August 9, 2014, when Ferguson officer Wilson pulled up and told them to use the sidewalk. In a grand jury deposition, Wilson testified he saw Brown holding Cigarillos and had recently heard a radio call about stolen cigarillos from a local market. He cut Brown and his friend off with his police car as they were walking.

A physical altercation began between Brown and Wilson at the police car’s driver’s side door. Wilson drew his gun, and a struggle ensued. Wilson fired shots but testified that his gun jammed several times. Brown began to run, and Wilson chased after him. Brown was not armed.

Brown eventually came to a stop, and Wilson stopped with him. Soon after, Wilson fired more shots at Brown, killing him. The officer fired 12 shots total, six of them hitting Brown.

Then-St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Bob McCulloch announced in November 2014 that a grand jury did not return an indictment against Wilson for Brown’s death. The Department of Justice declined to prosecute Wilson after conducting an investigation. St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Wesley Bell, who took office in 2019, also declined to prosecute the officer after a five-month review of the evidence.

When reached by phone, Wilson declined an interview for this story.

WATCH: Michael Brown Sr. recalls the day his son died 3u713

A court-appointed monitoring team — a of experts in policing, constitutional law remediation, and other areas of expertise — monitors the city’s progress in meeting the tenets of the consent decree and whether that translates to constitutional policing.

“The Monitor does not replace or assume the role or duties of the Chief of Police or any other City official,” deputy monitor Courtney Caruso told First Alert 4. “Rather, it provides technical assistance to the city, assesses implementation, and reports on the status of implementation to the court.”

Once the city has completed all the provisions of the consent decree, and the changes have been in place for two years, Ferguson will no longer be subject to federal oversight. There is no time limit to the decrees. While most lay out a five-year plan, historically that has rarely been the case.

Los Angeles was under a consent decree for about 12 years before it ended. Detroit saw about the same length, 13 years, to emerge from federal oversight. It took Oakland, California, 20 years to get to a place where it might end federal oversight. The record goes to Hartford, Connecticut, which spent almost 50 years under the court’s gaze before emerging on the other side.

With the Ferguson consent decree in place now eight years, when it might be free of federal oversight is a question on the minds of many.

“Until and when the city has moved all areas of the consent decree into the implementation phase, and the monitoring team determines compliance in those areas, the consent decree will remain in effect, barring an otherwise formed mutual agreement between the parties, and with the court’s approval, for early termination of a particular provision,” Caruso said.

DOJ attorney Amy Senier said during the July hearing while implementation is not where the federal officials would like it to be, progress is being made, adding it is “important for people to know that.”

“When does it end, what happens after it ends. Well, it ends by the of the Decree, when there is full and effective compliance and that’s sustained for a period of two years,” Senier said. “But to get there, it’s created remedies that are designed to be durable, and what that means is that FPD will end up an agency that is reflective, that is able to course correct without the oversight of DOJ, the monitor, or the court.”

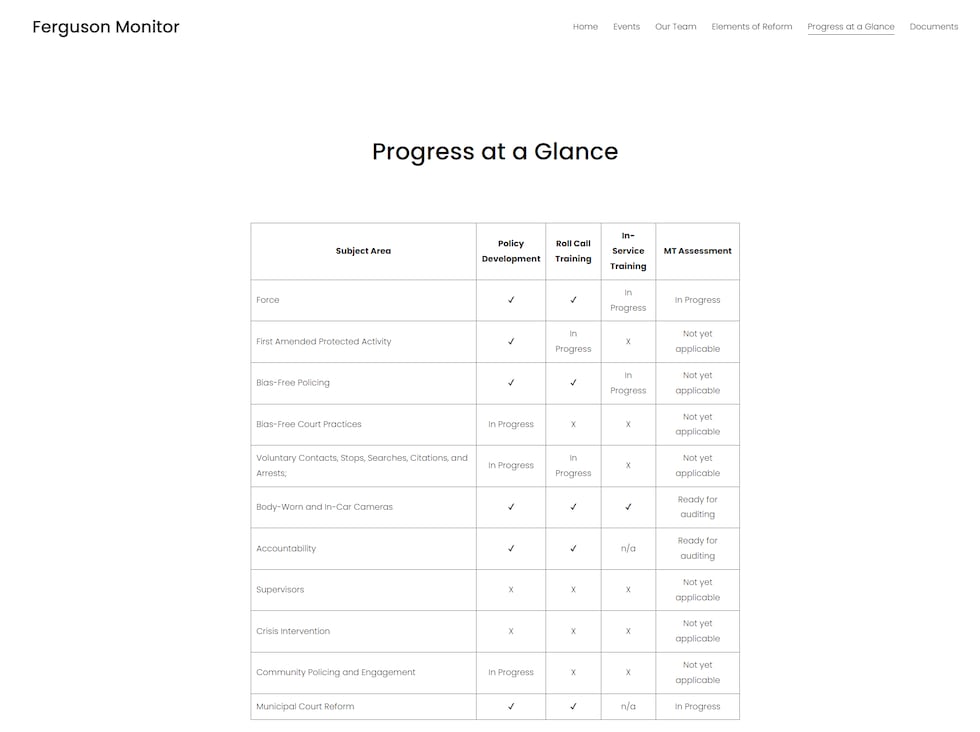

On its website, the monitor team lists areas for reform, as well as the city’s progress. They include community policing and engagement, use of force, First Amendment activity, use of force, body cameras, ability, municipal court reform and others.

Caruso said within those areas there are hundreds of provisions, divided into policy, training, and implementation efforts, each of which must be completed for compliance with the agreement.

“In general, the city has completed policy development in each of the key areas of the agreement with the exception of bias-free court practices, voluntary s, stops, searches, citations, and arrests; and community policing and engagement,” Caruso said. “Next, the city is responsible for both roll-call and in-service training of the policies, after which the policies are considered ‘implemented’ and the Monitoring Team begins its annual compliance assessments of those areas.”

“Few areas have completed both of these required trainings,” she said.

Ferguson Police Chief Troy Doyle told First Alert 4 that the consent decree was one of the most important things to come from the DOJ investigation. He also said many of the of the agreement have already been put into policy and training.

“All these things the DOJ is asking us to do, these policies have been implemented in the Ferguson Police Department,” Doyle said. “As I tell my officers each and every day, we have to look at the consent decree not as punishment, but as a document that will guide us to doing better policing in the community. And hopefully, when we get through this document the Ferguson Police Department will have some of the better policies and procedures throughout the whole region.”

ARCHIVE: Ferguson Police Chief Troy Doyle speaks on the consent decree as he is sworn in in March 2023 2m5630

Doyle said many of the provisions are not difficult to enact. One of the barriers is the extensive training required by the agreement.

“Nothing in the consent decree is difficult, it’s just timing,” Doyle said. “This is a small police department, we are not like a big 300 to 500-man police department, so trying to get everybody in a training course at the same time is somewhat difficult. We have to get subject matter experts to come in and teach our officers and sometimes there have to be multiple days.”

The monitor team agrees training has been one of the biggest challenges to fulfilling the agreement. In a t response, the team told First Alert 4 that is beginning to change with the recent hiring of a new training coordinator.

“Training remains a critical area of the consent decree that has often been the log jam between policy development and the monitoring team’s ability to assess implementation of those policies,” the team said. “For example, numerous policies in the areas of stops, searches, and arrests have been fully developed, but have not yet been trained on.”

Just because the provision has not been fully checked off, progress is being made and is visible, officials said. Of all the provisions in the consent decree, none has more public visibility than the implementation of community policing.

Community policing guides day-to-day law enforcement activities in the community. Beats are structured around specific neighborhood boundaries. Officer communication with residents is encouraged. Walking and bicycle patrols are encouraged, and officers are asked to provide residents with business cards and information.

During the July court hearing, Ferguson resident Becky Mueller commended the officers’ showing during Juneteenth events in the community.

“They seemed to exemplify good community policing,” Mueller told the court. “The officers looked like they were enjoying the event more and certainly interacting with the community better. Their deployment didn’t seem to diminish their ability to observe and respond to incidences that might develop either at events or throughout the community, and we appreciate their efforts to make this a positive event.”

Other items include the implementation of body-worn cameras. Ferguson began using the devices just weeks after Brown’s death, spurred by the lack of unbiased evidence in the fatal shooting. It was one of the first police departments in the nation to do so and many law enforcement experts have attributed the move to inspiring other agencies to follow suit.

Ferguson has also made changes in improving police ability, which was a serious issue in the department at the time of Brown’s death, according to the DOJ’s 2015 report. Given the department’s focus on generating revenue, constitutional violations by officers were often overlooked in the name of profits.

WATCH: First Alert 4’s Russell Kinsaul shows the results felt in Ferguson nearly a decade after the DOJ ruled its police and courts violated people’s Constitutional rights.

Every city employee must now report misconduct claims to a supervisor. The city must document all complaints of misconduct. It must investigate complaints and issue a finding and disciplinary action if applicable for the city employee.

The city’s new ability policies offer community mediation of some misconduct complaints. A professional mediation service will attempt to mediate between the complainant and the employee in question. Both parties must agree to the mediation and officers are only allowed a maximum of two mediation sessions a year.

It also requires Ferguson police officers to wear nametags on their uniforms and provide their names and badge numbers to of the public upon request.

First Amendment policies and procedures are another provision of the agreement, and one that the city seems to be gaining traction on according to Chris Crabel, who serves as the Consent Decree Coordinator for the City of Ferguson.

“So the City of Ferguson in collaboration with the Department of Justice will hopefully be finalizing the First Amendment policy, today hopefully, so that will be a good step forward,” Crabel told the court during the recent status hearing. “This is a significant milestone in our ongoing efforts to align our practices with the principles of free speech and public assembly, so hopefully we can wrap that one up today.”

The 2015 DOJ investigation found that Ferguson Police often violated citizens' rights guaranteed by the First Amendment, punishing them for talking back, lawfully recording police, and legally protesting.

In one instance in 2015, when a group was protesting outside the police station on the six-month anniversary of Brown’s death, two police cruisers accelerated into the street and an officer announced, “Everyone here is going to jail,” causing the protestors to run.

According to the Department of Justice investigative report, while the abuses heaped on the public by Ferguson Police were many, they were seemingly exceeded by the malfeasance of the municipal courts. The DOJ in its findings concluded that the top tier of the city justice system had become little more than a cash cow for the istration at the time.

The consent decree now prohibits the city finance division from interacting with operations. It altered the way warrants were issued to ensure due process and ended its practice of jailing people who could not afford to pay. The court offered an amnesty program on fees and fines before 2014 and now works with defendants based on their ability to pay.

While work remains on fulfilling the consent decree according to many officials associated with its implementation, according to Judge Perry, who will ultimately be tasked with deeming it fulfilled, everyone should be pleased with the progress made.

“We’re not perfect,” Perry said. “We have got a ways to go. As everyone knows, when we meet and talk, it’s how much longer will this go on and when can we get there, but we are getting there and the progress especially this year has been very good, so I’m hopeful that, you know, we’ll get to a point where you won’t need us to be doing this, but we are not there yet.”

Ferguson’s history with race before Michael Brown’s death g1b31

‘As many have said, it was a pot that was just ready to boil over’ - Jane Gillooly, director of ‘Where the Pavement Ends’ 54554i

By Dan Greenwald

Ferguson, much like the rest of the St. Louis area, has a history of formal and informal segregation. For most of its history, Ferguson was a majority-white town. It’s an old railroad suburb from the 19th century, its population significantly increasing after World War II.

“St. Louis had a long history of what is called redlining, certain neighborhoods were meant to be white-only or black-only, whether you’re talking about the real estate industry or the laws,” Christopher Gordon, Director of Library and Collections at the Missouri Historical Society, said.

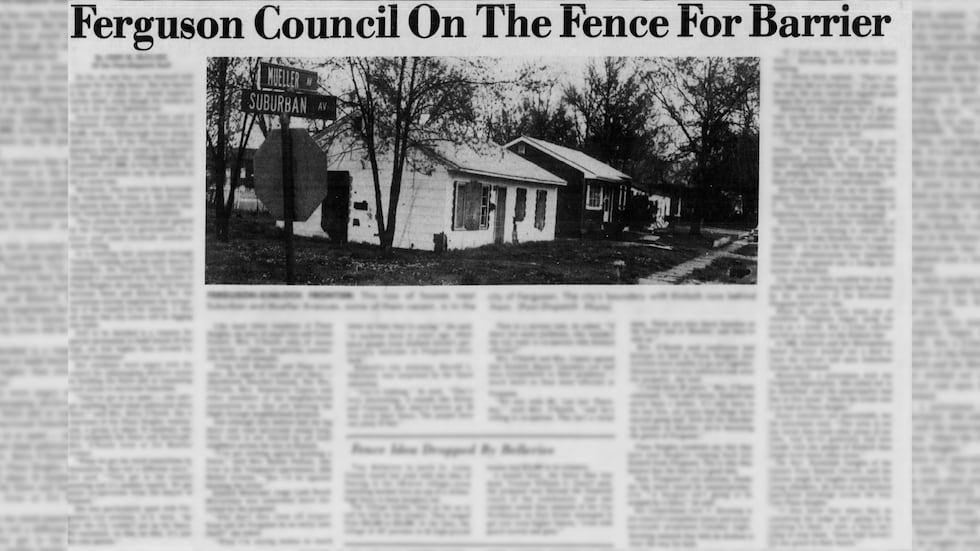

A few examples of this racial division can be seen in controversies from the 1960s and 1970s. Next to Ferguson sits Kinloch, the first city in Missouri incorporated by African Americans. One of the streets that connects Ferguson and Kinloch is Suburban Avenue, which forms the southern border of both cities. Ferguson placed barriers across the road to prevent people from driving into Ferguson from Kinloch.

In the 1960s, many residents and officials in Kinloch — and some in Ferguson — asked for the barrier to be removed. During a memorial march from a Kinloch church to a Ferguson church to honor Dr. Martin Luther King in April 1968, the barrier was breached.

“It was a transgressive act in some ways for the people of Kinloch to remove the barrier, and they had a right to take it down,” Jane Gillooly said. She made the film “Where the Pavement Ends,” which chronicles the racial divide in Ferguson and Kinloch.

A short time later, the Ferguson City Council voted to officially remove the barrier.

In 1975, Ferguson City Councilman Charles Kersting proposed building a fence along the border between the cities. He and allies cited rising burglaries. Opponents said it was racially motivated. One plan called for a 10-foot high fence, another proposed allowing Ferguson residents who lived along the border with Kinloch to receive interest-free loans to build their own fences. The proposals were the subject of protests. Neither plan ed.

“The attorney for Kinloch said ‘we’ll jump over the damn thing,” said Dr. John Wright, the former Kinloch School District Superintendent. Wright is the author of “Kinloch: Missouri’s First Black City.”

“There was a period of time where tensions kind of rose in the community,” Wright said.

Within a few decades, the demographics of Ferguson would start to change. The city became majority Black in the 2000s as white residents moved out, a pattern of racial division that Wright says was typical in the St. Louis area and similar to what happened with white flight from St. Louis City after World War II.

“The attitude is there, it is pervasive…there is a feeling that is quite pervasive. Once they started building homes in North County, whites moved from the city feeling they were freeing themselves from Blacks,” Wright said.

Gillooly said the history of racial division and police conduct associated with it led in part to the protests in the aftermath of Michael Brown’s death.

“People have long ed their experiences and how they had been treated and shared these stories with their children, creating a collective memory of the region,” Gillooly said. “Given the long-standing racial divide and the segregation of communities like Kinloch, it didn’t surprise me that protests erupted (after Brown was killed). People carry the history of trauma and injustice with them. As many have said, it was a pot that was just ready to boil over.”

The role of body-worn cameras at police departments post-Ferguson 2x1v3k

By Matt Woods and Lucas Sellem

Ferguson became one of the first St. Louis-area police departments to utilize body-worn cameras, starting weeks after Brown’s death. Today the technology is commonplace in police departments locally and across the U.S.

A First Alert 4 inquiry found that the 25 largest police departments in St. Louis County and City have started using body-worn cameras since Ferguson implemented its program. SIUE Criminal Justice Professor and Director of its Center for Crime Science and Violence Prevention, Dennis Mares, studies police use of body-worn cameras and other technology.

He said one of the advantages of the cameras is having unbiased evidence for incidents that include use of force. But there are also limitations, like a narrow field of view.

How the circumstances around Brown’s death could have been different with a body-worn camera is something Mares said he can’t speculate on. However, he said it may have changed the aftermath.

“If you don’t have footage of an incident like that, you leave the public to speculate about these things,” he said. “And that’s never a good thing.”

Mares said he believes body-worn cameras are a good ability tool if they are used properly. That comes down to policy and training, something the Ferguson Police Department was required to implement under its consent decree with the DOJ.

Through his research, Mares has found officers can be hesitant about body-worn cameras before using them. After the implementation of the cameras, Mares said, officers were generally much more positive about the benefit for the public and themselves.

“I think it helps on both sides,” Mares said. “It helps the public if the police officer really did something wrong.”

Mares is working on a project with the Alton and East St. Louis Police Departments to evaluate the effectiveness of the departments’ body-worn cameras. Both departments received a grant from the Bureau of Justice Assistance to help pay for the equipment. The project includes interviews with officers and the general public and analysis of use-of-force data.

Adding body-worn cameras costs police departments roughly $2,000-$2,500 a year per officer, Mares said. Most of the cost is associated with data storage.

Mares said he doesn’t believe the media has properly featured the strides made in policing in the last decade despite the viral use-of-force incidents that leave the public shaking their heads.

“Particularly the police chiefs in our region have started to see this, that it is important that you reach out to the community, that you do provide a degree of transparency to the community in a variety of ways,” he said.

Rebuilding Ferguson after 2014 1m1w3i

By Alexis Zotos and Josh Robinson

In the days following Brown’s death and the night of the grand jury decision, many businesses in two North County communities were destroyed. But a decade later, many of those businesses rebuilt and helped bring a revitalization to the region.

Juanita Morris watched on TV as her shop Fashions R Boutique in Dellwood went up in flames. Several businesses around it were burned to rubble.

“Everything I had worked on for 28 years went up in smoke,” said Morris.

She rebuilt and reopened a few miles away.

All across the cities of Dellwood and Ferguson, where the majority of the unrest took place, is a story of rebirth.

“Now we have a community in Ferguson where you can walk, you want some ice cream, you want a smoothie, you want some BBQ?” said Jerome Jenkins, co-owner of Cathy’s Kitchen.

His wife, Cathy, whose namesake restaurant sits just doors from the Ferguson Police Department, said 10 years ago was a scary time but she also understood the anger and frustration bubbling up in their hometown.

Dozens of new businesses have opened. Cathy’s Kitchen expanded with a second location and on the site where Morris’ shop burned, an $8 million development will break ground on August 9 — a decade to the day since Brown’s death set off a movement that changed the community and the world.

The Ferguson-Florissant School District made it a priority to push a good education for students after Brown’s killing.

When Joseph Davis became aware of the situation while at home in North Carolina, he wanted to make a difference and applied for superintendent at the district. He got the job in 2015 and has been there ever since.

“I came here because of it so it’s deeply personal for me,” Davis said. “It’s a microcosm of what’s been going on around our country, especially around race. And I think we have to really grapple with the conversations about race, especially for Black men in America living and walking in these shoes every day. It’s a different experience.”

Davis moved to Ferguson during those events, witnessing the Department of Justice’s decision to not prosecute officer Wilson. Davis wanted to bring awareness to the students in the district. He says the way to sustain change is through policy, laws, and ordinances.

“We’ve done a lot of work over these last 10 years with municipalities, with different nonprofit agencies to the growth and development and done some things on our school board,” Davis said.

With Davis’ help, there has been some change in the Ferguson-Florissant School District. The district provided SROs in the schools and built a relationship with local officials in the area.

Along with building relationships, Davis contributed to the district by making the students a high priority.

“We want to prevent what happened to Michael Brown. And the best way to do that is to make sure every child gets a quality education,” Davis said.