How does FEMA approve disaster funds? Complicated story, but we have a clue

Uncertainty about federal disaster aid looms as multiple states prepare to clean up devastating tornado damage

This article includes reporting and contribution from a number of reporters and outlets along the Mississippi, including Phillip Powell (Arkansas Times), Lucas Dufalla (Arkansas Democrat-Gazette), Cassandra Stephenson (Tennessee Lookout), and Illan Ireland (Mississippi Free Press).

ST. LOUIS, Mo. (First Alert 4) - It’s now been a week since the devastating May 16 tornado cut a path of destruction from Clayton to North City, a major question is emerging — how does FEMA approve funding, and how long will it take?

That’s a nuanced question, and the answer is a little complex.

The short answer is that the city, county, state and federal governments must work together — and independently — to assess damage. This can take weeks or months before making proposals to higher offices, including the Oval Office.

However, we may have a way of estimating and comparing the FEMA application process and time by looking at the last severe and deadly tornado that came through the St. Louis Metro area — the six tornadoes that crossed Missouri on March 14.

In fact, it was this Friday that President Donald Trump officially approved federal disaster assistance for those tornadoes in March.

Disaster assistance and declarations were made by that storm and tornado the day after the disaster, and now, two months later, many questions are left unanswered, including how much money will eventually flow to those impacted.

MARCH 14 TORNADO & COMPLICATIONS

When the March 14 tornadoes hit Missouri, the death toll and path of destruction were much wider spread across eastern portions of the state. In the St. Louis metro area, trees were flung into houses, tornadoes destroyed homes in suburban areas, and just over the bridge, an Illinois school had the roof ripped clean off.

One family, the Coles, in Bridgeton, was the only family on the block to have their entire home decimated by a tornado. Despite living on a residential street, surrounded on all sides by other homes, only theirs was torn apart by the storms.

“Where are we going to live?” Tammy Cole told First Alert 4. The family had been in the house for about a year, and had gone to visit family — luckily, they weren’t home when the storm hit the house.

They arrived after dark to scenes of police tape and a house falling apart. With neighbors’ help, they scoured the wreckage and the neighborhood for their two cats and a bearded dragon that were home when the tornado hit.

Somehow, all the animals survived, but much of the rest of the house was totaled. Tammy was quiet and calm standing in the remains of her living room — now just a box with destroyed insulation blowing in the breeze of the broken door.

Outside, her oldest daughter, a high schooler, was thinking back to her birthday. It was the day before the storm on March 14. The night the storm took her house, she was planning to have a sleepover with friends.

She was ionate when she said, “They called me and said the house is gone… This messed up my birthday weekend, but I don’t care ‘bout my birthday – I’m alive though. My family is alive. The animals are alive. I wouldn’t be able to have a birthday weekend if we were here.”

The father, Marcus Cole, told First Alert 4 that the work of 17 years was taken out in an instant.

Across the street, their neighbor’s home was standing mostly undamaged.

The death toll rose above 30 across multiple states, 12 of those in Missouri.

Some residents in St. Louis were shaken up by the tornadoes in the city and county itself. An anonymous lift-share driver said he’d never heard of them in areas like Carondelet – an area populated since 1767. Many areas had severe damage – in total, Governor Mike Kehoe (R) named 25 counties statewide in an official communique. Kehoe said FEMA would be part of “t Preliminary Damage Assessments” on public infrastructure in those counties.

The governor was prepped for some sort of disaster before the actual storms even hit. On March 14, he issued Executive Order 25-19, recognizing the potentially devastating impact of the storm and declaring a state of emergency and activating the state’s Emergency Operation Plan.

The massive storms on March 14 came only two days before the 100th anniversary of the deadliest tornado in Missouri history. In 1925, nearly 700 people died in the infamous Tri-State Tornado, leaving a 200-mile path of destruction and death from Ellington to Indiana.

Farms, homes, schools and lives completely destroyed — an echoing story 100 years later.

Farmers in Illinois and Missouri say they’ve lost plenty of equipment and acreage, while city folks say their roofs are in serious disrepair. KMOV-TV spoke with dozens of folks who lost homes and loved ones in the destruction.

While tornadoes didn’t reach that 1925 level, at least six touched down in the St. Louis area alone. That was alongside reports of hail, wind gusts over 80 miles an hour and rapidly changing rain and weather.

Kehoe’s official announcement of the work with FEMA included a promise that other counties could be included if the damage was deemed severe in other locations.

He’s not alone. The two representatives for Missouri — Wesley Bell, a Democrat, and Jason Smith, a Republican — both lead a delegation to urge federal disaster declarations following these tornadoes.

“The damage from the deadly March 14 tornadoes is devastating, and communities across our state are in urgent need of federal ,” said Rep. Bell. “I urge the President to grant Missouri’s emergency declaration request without delay so we can continue to rebuild and recover.”

The letter was also signed by Missouri Representatives Ann Wagner (R), Bob Onder (R), Mark Alford (R), Emanuel Cleaver (D), Sam Graves (R), and Eric Burlison (R).

Missouri’s own agency, the State Emergency Management Agency (SEMA) has been looking into the “hundreds” of homes and businesses impacted by the storm and debris, according to the Governor’s Office. They also noted severe damage to critical infrastructure, bridges, roads and other pathways.

In their initial assessments, officials identified at least 368 destroyed houses. All but 12 were considered “major damage” under SEMA standards. Over a thousand other homes in Missouri alone suffered minor damage.

In a statement, Kehoe said SEMA was quickly out collecting data on the ground with local officials to “document damage, collect cost estimates and substantiate the need for federal Public Assistance. Initial damage reports clearly warrant a formal review by FEMA as part of the disaster declaration process.”

Six teams went out ing and documenting the impacts — to see if the local destruction will actually reach the level of FEMA requests — and also to look at state state-level response.

Of the 12 tornadoes known to have touched down that weekend in Missouri, there were three EF-3 tornadoes, five EF-2, and four EF-1.

Kehoe even asked for more following the disasters, including directly to the White House. “Governor Kehoe has been in direct with the White House and [FEMA] officials, who have assured him they are closely monitoring the situation and are ready to assist as soon as Missouri request is submitted.”

Severe weather has been fairly common in the last six months across the entire Show Me State. In fact, former President Joe Biden authorized major disaster declarations for Missouri in January of this year. His approval recognized the severe impacts of cost-sharing and hazard mitigation measures for 14 different counties, due to extreme wind and flooding.

But how – and when – presidents approve FEMA funding seems to be getting more and more politically divisive.

FEMA POLITICS

A number of other states have faced tornado, high-line wind, flooding, wildfire and other natural disasters in the past few months – all facing challenges accessing FEMA funds and recovery .

One of those states is Arkansas, our neighbor to the south. During the same series of storms that struck St. Louis and Missouri in March, Arkansas was badly hit.

“I didn’t even know there was a tornado on the ground until the sirens went off, and then in 45 seconds it was here,” Cave City, Arkansas, resident Debra Lindsey said. “It was very scary. If it would’ve been 100 to 150 feet closer to here, it would’ve taken the front of our trailer off.”

She’s a retiree who lived in a trailer home with her husband when the March tornado struck.

Even without a direct hit, she estimated that the damage to their home and property was between $30,000 and $40,000. Their storage buildings were destroyed, along with their two vehicles. And the insurance company won’t cover everything.

Across the street, Robert and Kymberlie Watson sat out the tornadoes with their seven children in the nearest storm shelter. When they returned, they found roughly $60,000 worth of damage to their property.

About one month after the tornadoes, the Trump istration denied Arkansas’ request for a major disaster declaration. The declaration would have brought federal funds into the state to help with recovery. Both families thought they’d have to pay out-of-pocket for repairs.

The power to grant a disaster declaration and access to the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s assistance programs lies solely in the hands of the president, and President Donald Trump’s istration is looking to significantly scale back FEMA and disaster recovery costs onto states.

Over the past two years, the Biden istration provided more than $101 million in public disaster recovery funding to Arkansas, according to FEMA data. And before that, the first Trump istration gave Arkansas more than $101 million in federal disaster recovery assistance between 2017 and 2020.

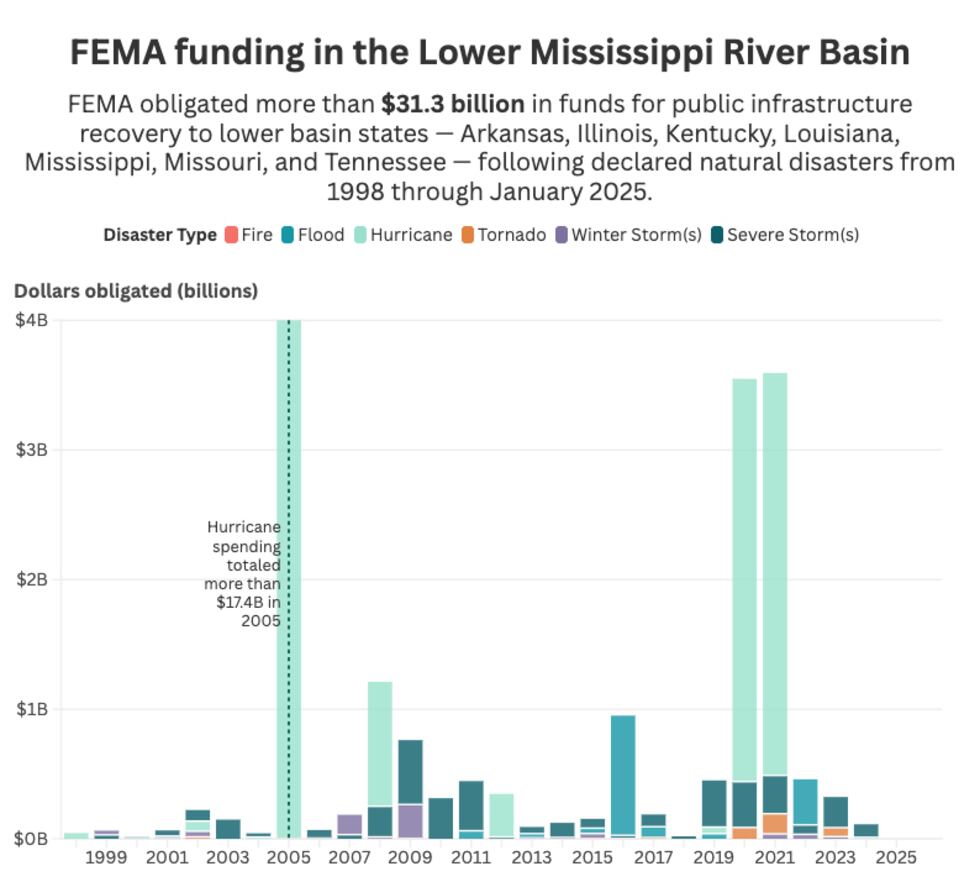

States in the Lower Mississippi River Basin have received more than $31.3 billion in federal public recovery assistance following natural disasters since 1998, according to FEMA data. Hurricane response has consistently required the most federal assistance.

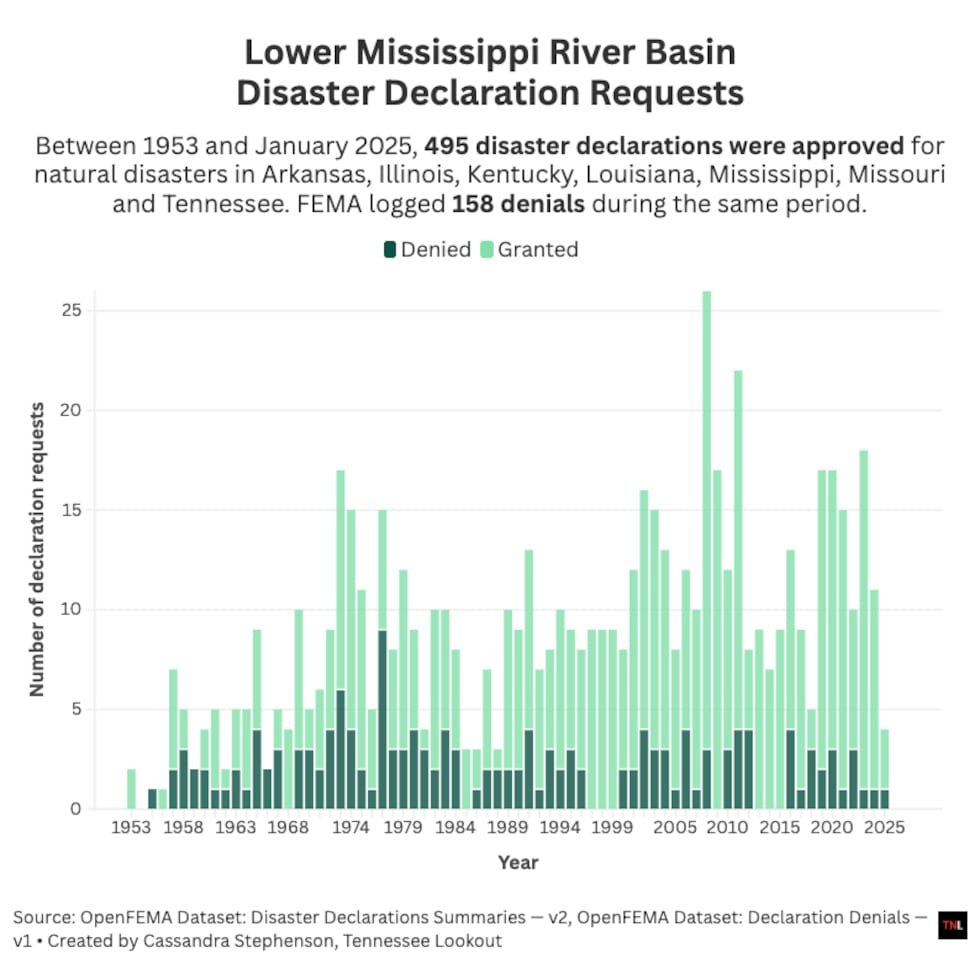

In recent years, there have been more requests for disaster declarations, and more of them have been approved than denied. Between 1953 and 1999, Lower Mississippi River Basin states saw two approvals for every one denial. Within the last 25 years, the approval ratio rose to 5-1.

John Gasper, an associate professor of economics at Carnegie Mellon University’s Tepper School of Business, found in a 2015 analysis of county-level FEMA data from 1992 through 2005 that the chance of a denial is lower when the president and governor belong to the same political party. In “non-election years or non-opportune times,” denials typically follow FEMA’s unofficial guidelines, he said in a May interview.

There are two reasons for FEMA aid’s president-centric policy design, Gasper said: the federal government wants the ability to grant aid in “marginal cases that don’t make the threshold but still are clear disasters,” and politicians realize the benefits of giving aid to constituents.

“In an election year, it’s a great opportunity for a campaigning official to come in, do photo ops, roll up their sleeves, etcetera,” he said. “In non-election years, they have less concern there, so the probability of denial goes up substantially.”

The denial of Arkansas’ initial request for help was “shocking,” said Anderson. Sanders, who worked as press secretary for President Trump for part of his first term, credited her access to the president for her appeal’s eventual success.

Changes at FEMA have further muddied the process of requesting and obtaining disaster assistance. Since January, the Trump istration has dismissed hundreds of FEMA employees and scrapped an agency program funding disaster prevention efforts in states and municipalities. The Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program has made $5 billion in grant money available since 2020, awarding over $12 million to Arkansas, Mississippi and Tennessee through 2023.

Federal officials have also discussed making it harder to secure funds after a disaster. In an internal memo obtained by CNN, former acting FEMA Cameron Hamilton proposed various reforms to curb the agency’s disaster spending, including quadrupling the financial burden states must sustain to qualify for public aid. Hamilton was fired weeks later, and state officials say they have received no word regarding changes to FEMA’s public assistance threshold.

While the higher benchmark proposed by Hamilton has not been adopted publicly, the low number of disaster declarations approved so far this year suggests the White House is following new standards for public aid eligibility, one emergency management expert explained.

“We don’t have to wait for an official guidance on this. We know that the bar has shifted,” said Bryan Koon, who led Florida’s Division of Emergency Management from 2011 to 2017 and is CEO of IEM, a disaster management consulting firm. “What got you a declaration in 2024 and earlier is not going to get you a disaster declaration in 2025.”

Hamilton’s replacement at FEMA, David Richardson, reportedly held a meeting with staff where he said a large part of the response and recovery would be put on states under his leadership, according to Drop Site News.

Bipartisan for disaster aid reform does exist, but Trump’s FEMA overhaul has sparked concern among state emergency management officials, who say they aren’t prepared to take over disaster funding responsibilities from the agency.

Such a transition would require extensive guidance from the istration and planning from state and local governments, said Lynn Budd, president of the National Emergency Management Association and director of Wyoming’s Office of Homeland Security. Reducing FEMA assistance with little clarity or advance notice risks leaving communities unprepared for disasters moving forward, she added.

Even with clearer messaging from the istration, scaling back FEMA would require states to make tough choices on how to cover disaster costs and budget for future emergencies, Koon explained. Reallocating funds toward disaster management would mean cuts to other services, and states would have to lean heavily on volunteer organizations to fill financial and staffing gaps.

“States are going to have to adapt,” Koon said. “It’s going to be a lot more of a patchwork of to make up for what would have come from the federal government.”

Koon emphasized that shifting disaster expenses to states would also mean higher costs for residents. Households will have to purchase broader insurance coverage in the absence of FEMA assistance, he explained, and families will have to pay for damage previously covered by the agency.

In Mississippi, where residents are still recovering from the same storms and tornadoes that struck Arkansas in mid-March, emergency management officials said they will continue looking to FEMA for disaster assistance until they are instructed otherwise. The state is awaiting a decision from the White House on its own disaster declaration request, and officials said they won’t adjust operations or request additional funding from the legislature without more guidance from the istration.

“We have received no indication from FEMA about any proposed changes to formulas that determine federal disaster assistance,” said Scott Simmons, director of external affairs at the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency. “Until the rules of the game change, we’re going to continue playing by the rules.”

Others are looking ahead at how states could respond if FEMA steps back.

States already play active roles in recovery but they “need to become a little bit more proficient and get help in coordinating and answering disasters together,” Colin Wellenkamp, executive director of the Mississippi River Cities and Towns Initiative, a coalition of more than 100 mayors of river basin cities, said in early April following severe flooding along the river.

Flooding on the Mississippi River typically impacts all of its 10 bordering states, he said, so if states do take on more responsibility, they would need to work “in tandem” to coordinate recovery efforts.

“That isn’t necessarily something that happens through the FEMA process,” Wellenkamp said.

A new round of storms and tornadoes swept through the basin in mid-May, leaving major damage in St. Louis, Missouri. And hurricane season begins June 1. Researchers are predicting above average activity this year.

With the Trump istration’s new approach to FEMA aid, Anderson worries that recovery for small places like Cave City may become even harder.

“There’s just things the Federal government has been or should be doing…they’re just a lot more equipped to handle that than a city or a state,” Anderson said. It’s an imperfect process and he added that “numbers on a spreadsheet don’t always tell the human story.”

OTHER STATES & STRUGGLES

For other state residents, like Debra Lindsey in Arkansas, the future looks a little uncertain. Not only was she a retired nurse, she’s also disabled. But with the storm, the damage, the costs — and the impact — she’s afraid that if federal assistance doesn’t flow into Cave City — she may have to reenter the workforce.

Another round of severe weather walloped the Lower Mississippi River Basin in early April, causing extensive flooding and more tornado damage in parts of Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky and Mississippi.

Then, some good news: the Trump istration reversed course on May 13 after an appeal and a personal plea from Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders. The president granted a major disaster declaration, allowing individuals like Lindsey and the Watsons to apply for aid.

“If we get some help out of it, that’s absolutely amazing. We could really use it,” Kymberlie Watson said. “We’re surprised, a little bit … because the government actually stepped up and helped its citizens.”

Cave City may not be so lucky. Trump has yet to approve recovery assistance to public entities, which may leave local governments — including the town of less than 2,000 residents — with big bills. On May 3, Sanders submitted another disaster declaration application asking for extensive public assistance. Requests for FEMA aid from Mississippi, Missouri and Tennessee also remain outstanding, though the Trump istration did grant Kentucky’s request.

“President Trump and his istration will continue working to further empower state and local governments to build their own resilience before disaster strikes and to execute rapid, smart response when supplemental federal assistance is required to truly protect citizens and aid a return to normalcy,” a White House official wrote the Desk by email.

Cave City Mayor Jonas Anderson was at a ribbon-cutting event for the city’s ambulance service when he learned of the initial rejection from the Trump istration. His first thought?

“You have got to be kidding me,” he said.

Anderson estimated that some 50 Cave City homes were damaged in the March tornado, and 25 of those were completely destroyed. He said underinsurance was likely a huge issue in the community, and the costs for the city to remove all the debris might run over $300,000 for a municipality that only has an annual budget of around $1.4 million. Cave City also lost its only grocery store, forcing residents to drive 20 to 30 minutes to nearby towns for necessities.

A disaster declaration opens up potential programs for state and local governments to recoup some money spent on removing debris and repairing infrastructure. It can also unlock assistance programs for individuals, including post-disaster services and financial aid for people who are uninsured or underinsured. Not all programs are offered for every disaster.

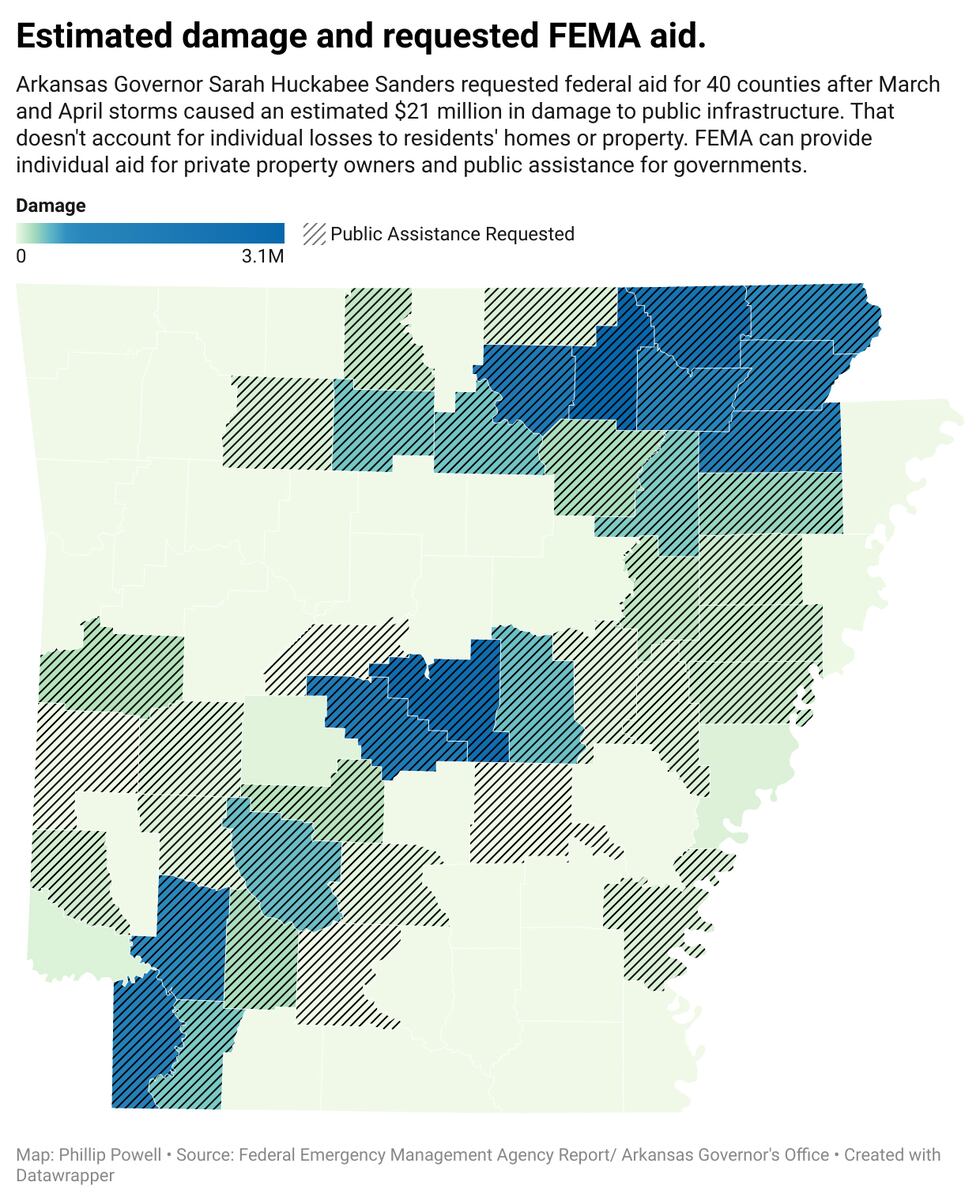

After a disaster, government personnel assess the cost of damage. Sanders’ requests for federal disaster aid for dozens of counties mostly in the Arkansas Delta estimated public damages at over $21 million from both the March and April storms, including more than $3 million in Sharp County, home to part of Cave City.

FEMA uses cost per capita to gauge whether local and state governments can handle recovery themselves, or if they’ll need federal help. Those thresholds currently stand at $4.72 per capita for counties and $1.89 per capita for states. Per capita damages for Sharp County, where Cave City is located, are estimated at $179.

But meeting those thresholds does not guarantee that the president will approve a disaster declaration. A president is not required to justify their decision, and documentation of the reasons for denial is considered privileged, not public record.

Sanders released a statement thanking the Trump istration for finally delivering individual assistance, but did not mention her second, outstanding request for public assistance and additional funds. She also expressed for Trump’s efforts to reform FEMA.

“Our entire state is grateful for President Trump’s leadership and assistance as we recover from the devastating storms that struck Arkansas earlier this spring,” Sanders said. “I had a productive conversation with the President in which he expressed his for our state and I offered my full endorsement of his plans to reform FEMA to save money and provide greater direct assistance to disaster victims.”

This story is a product of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri in partnership with Report for America, with major funding from the Walton Family Foundation.

Avery Martinez covers water, ag & the environment for First Alert 4. He is also a Report for America Corps member, as well as a member of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk. His coverage ranges from EPA s to corn farms and hunting concerns, and local water rates to rancher mental health.

Copyright 2025 KMOV. All rights reserved.

![[Insert Caption Here]](https://gray-kmov-prod.gtv-cdn.com/resizer/v2/JA6563POYVBLLK7VJBLDIMBZQY.jpeg?auth=e3bd3bb8728979ec3fcde73feaaf628b9e20b1be20c13edc8a5f4436501eb89d&width=800&height=450&smart=true)