St. Charles County used opioid remediation funds to pay death investigators and filed it as treatment

ST. CHARLES COUNTY (First Alert 4) - St. Charles County allocated $148,000 in opioid settlement funds for connecting people with Opioid Use Disorder to treatment services. A First Alert 4 inquiry found the money went to cover two death investigator salaries at the local medical examiner’s office.

The county’s required public disclosure shows the recipient as the St. Charles County Medical Examiner Department with a description of “Regional Medical Examiner.” The spending category is listed as Connections to Care, under the umbrella of treatment.

Connections to Care is described in the settlement agreement as helping people who have Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) get care. St. Charles County Executive Steve Ehlmann justified using that money to pay for death investigator salaries in an interview with First Alert 4 Investigates.

“We were very careful to make sure we knew this was going to the right place and consulting people who knew a lot more about the problem than we do in this office,” he said, “including our law enforcement people and our not-for-profit agencies that deal with this.”

Ehlmann reasoned the spending from a law enforcement perspective. He said the death investigators can find information that leads police to drug dealers or find other people involved with the same group using drugs.

“If you can find out more about the supply and shut it down, that’s certainly I think a legitimate reason to spend this money,” he said.

The county lawyers reviewed the expenditure before it was made, Ehlmann said. Other than death investigator salaries, the county’s settlement spending includes $66,000 for a peer recovery specialist salary, $6,500 for a Teen Drug Summit speaker, and $7,500 for T-shirts to give the summit’s attendees.

A $2 million expansion of the jail to boost OUD treatment is in the planning stage, according to county officials.

State’s attorneys general settled the opioid lawsuits with drug makers, distributors, and pharmacies because of the overprescribing of addictive opioids that proliferated the overdose epidemic across the country. More than $200 million has landed in Missouri and about 150 of its localities, with about $700 million more projected.

Advocates emphasize treatment demand

April 30 would have been Nick O’Toole’s 27th birthday. His mom, Jill O’Toole, became an advocate for drug s during her son’s fentanyl use and after his overdose death in 2020.

She went to Jefferson City to advocate for Missouri’s opioid settlement before it was finalized. She said funding death investigators is not what the settlement was intended for.

“Dead people can’t recover,” she said.

The latest overdose death data shows there were 1,948 in Missouri in 2023. Partial data from 2024 showed a 23% decrease for the first half of the year, a sign of progress in addressing the epidemic. Nationally, the trend is similar.

Dr. Fred Rottnek did litigation work on opioid settlements and works with municipalities on how the funds can be spent. The death investigators’ salaries being supplemented with money earmarked for opioid remediation worried him.

“It’s really tempting to use opioid litigation funds to plug budget gaps, because that’s what we’ve done in Missouri with tobacco settlement funds,” Rottnek, the head of Saint Louis University’s Addiction Medicine Fellowship, said.

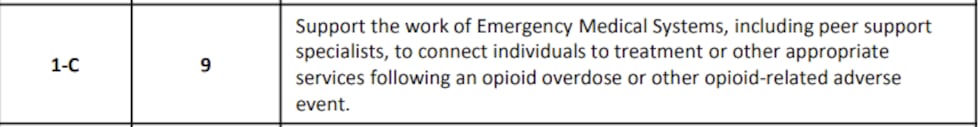

None of the approved use subsections in the settlement agreement specifically mention death investigators or medical examiners. St. Charles County officials cited a subsection that details ing the work of emergency medical systems.

Nick O’Toole started taking pills when he was 14 and went to rehab for the first time when he was 15. He started working at a factory after graduating high school, where Jill O’Toole said he got introduced to meth and fentanyl.

She came home from work on Jan. 22, 2020, and found her 21-year-old son dead in his bedroom after overdosing on fentanyl. On what would have been her son’s 27th birthday, she ed Nick as a practical joker who was into skateboarding and BMX. She also spoke about what he never got to achieve.

“He would have made the best dad,” Jill O’Toole said. “He loved his nieces so much.”

She is outspoken about the need for better access to medical treatment for substance use disorders.

Rottnek pointed out that while the medical examiner’s office does important work identifying drug trends, the treatment category is a stretch for funding death investigators.

“Calling it treatment is really not what is generally considered treatment in healthcare, and particularly with opioid settlement funds,” he said.

Searching for oversight, ability

First Alert 4 Investigates’ reporting on opioid settlement spending revealed avenues for ability are uncertain despite settlement reporting requirements and a 2023 state law on how the funds can be used.

Missouri and participating localities signed a memorandum of understanding agreeing to use the money for treatment, prevention, harm reduction, and a few other abatement strategies, and to make the spending public.

The state legislature also ed a law mandating the funds be used for “costs related to opioid addiction treatment and prevention.” The law does not designate an entity to enforce it or include a penalty provision for violations.

The Missouri Department of Mental Health (DMH) aggregates the reports and publishes them every March.

“We would hope that all entities are spending the funds to help those who have struggled or are struggling with opioid use disorder,” Lori Strong-Goeke, DMH’s opioid settlement reporting coordinator, said.

The funds municipalities receive do not flow through the state, according to Strong-Goeke, and there isn’t a requirement for the department to police localities’ spending after the fact.

After First Alert 4 Investigates reported Kirkwood used $30,000 in opioid settlement funds to cover half the cost of a Ford F-350 snowplow, Missouri Auditor Scott Fitzpatrick initiated an investigation. He told First Alert 4 part of the focus was to find out who is tasked with enforcement.

St. Charles County is set to receive an additional $11.8 million in opioid settlement funds. It has spent about $228,000 of its $7.8 million, just under 3%.

“There may be better uses, and we’re always open to suggestions about – when you go talk to everybody else about this — think somebody else has got a better use of it — give me a call,” County Executive Ehlmann said.

Statewide, 20% of the funds received have been allocated.

Copyright 2025 KMOV. All rights reserved.